Behavioural Architects removed people’s favourite brands from their lives to see what difference it made. The results, here in a series of short films, are astonishing and highly entertaining.

In Brief

We tend to think of humans as rational beings, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Decades of behavioural science has proven that most of what influences our thoughts and actions lie deep beneath the cognitive radar.

Part of the reason for this is practical. We are simply unable to process the mind-boggling number of decisions we need to make over the course of a day. In fact, neuroscientists estimate that we absorb around 11 million pieces of information every single second, but consciously process just 40 of these! So inevitably, we rely on a series of mental shortcuts, i.e. intuitive - or ‘system one’ to give it its technical name - thinking. Our rational mind is often employed as a way of validating the decisions that we’ve sub-consciously made.

Of course, this phenomenon is particularly true when it comes to brands. We tend to default to products and services that we know, we recognise or have experience of (known as heuristics). We also have a host of cognitive biases - such as the need to follow what other people are doing - and are hugely influenced by what is going on around us. Advertising is, and always has been, a way of ensuring brands remain top-of-mind and desirable in the eyes of the consumer. It helps lay down valuable, brand connections deep below the surface of our awareness.

But how does this theoretical relationship manifest itself in the real world? We sought to gain a deeper understanding of what brands mean to us and the role that they play in our lives. By depriving individuals of some of their favourite brands, we were able to use behavioural economics to surface how brands operate at a subconscious level, and what happens when we lose them!

Key findings

- Brands bring colour and connection to people’s lives.

- Branding primes the user to a more positive customer experience.

- Advertising, particularly TV, helps embed positive brand connections in the subconscious of the consumer.

- People make snap judgements about products and services based on branding. Brands ‘anchor’ perceptions of quality.

- Strong branding can positively impact the physical experience with have with brands.

- Brands bring stability to people’s lives. People feel their loss keenly.

Methodology

The Behavioural Architects designed a fascinating social experiment to demonstrate what branding means and the implicit impact it has on our perceptions of quality and our purchasing decisions. Often, the connections we have with the things around us are so entrenched that they become subconscious – we only notice them when they have gone. Through depriving consumers of their most cherished brands, we could start to surface how those brands bring meaning into people’s lives.

Twenty participants completed a ‘life logging’ exercise to document all of their brand contacts and allow us to identify which of those were the most pertinent in their lives. Each recruit was then deprived of a couple of their most cherished brands for a fortnight and a sent a ‘substitute’ to use instead. In most cases, this was exactly the same product – anything from tea, shampoo or fabric conditioner - but cleverly disguised in neutral packaging. The participants were unaware the products were identical and most assumed they had been sent a different brand to ‘test’. In other instances, the respondents were sent to alternative retailers or had their cherished cars ‘de-badged’. The recruits filmed their thoughts and experiences across the fortnight and were interviewed extensively before the experiment and after it had finished.

The Theory

Brands don’t just appear. Brand equity is in no small part derived from the carefully crafted marketing messages that, with time, help lay down deep subconscious brand connections. With each exposure, these brand lay-lines are reinforced and brought to the fore. Alongside the conscious associations we have about brands, such as the name, logo, taglines etc, there are a host of associations that sit beneath the surface. These could be visual, verbal or could tap into our emotions or beliefs about that brand. Ultimately, they shape our opinion of what the brand means to us, what it says about us and what it communicates about itself.

All of this has a significant influence on our behaviour and whether or not we’ll choose to identify with, and indeed invest in, one brand over another.

What role does TV play in building these brand associations?

TV advertising is powerful as it leverages certain cognitive biases almost immediately, often before deeper brand connections have been built. This primarily works in three ways:

- Mere exposure effect: Generally, the more we see something, the more positive we feel about it. TV generates some of the highest levels of exposure and frequency of any media and can therefore generate brand likability through increased familiarity. It’s one of the reasons you’ll see ‘as seen on TV’ slapped on product packaging.

- Recency effect: We tend to place greater importance on things that we have encountered more recently. Again, the heightened visibility of a TV campaign can serve to boost this bias.

- Social proofing: We are social creatures who have an automatic tendency to imitate how other people think and act. Advertising plays a crucial role in ‘normalising’ behaviour towards certain brands. TV is particularly effective at driving social norms due to its audio-visual nature – we can see and hear how others respond to the brand.

But the benefits of TV – and indeed advertising in general – are far more complex. Our research helped us identify some of the key benefits.

Findings

Brands bring colour and connection to people’s lives

Almost immediately, we witnessed the colour that brands bring to people’s lives. Our respondents were able to talk about their relationship with their favourite brands, what they loved about them and why. It was, however, clear that these connections ran deep and that the associations they held at a subconscious level were significantly impacting upon their behaviour and attitudes.

These connections manifested themselves in several key ways:

Priming:

As soon as we deprived individuals of their brands (remember, that the substitutes we gave them were exactly the same), the subconscious associations built over many years started to bubble up into the consciousness. By taking away the branding, our respondents were negatively primed to dislike the ‘replacement’ brands. There was no enthusiasm for the task – in fact some found the prospect quite distressing. One lady wondered ‘what was in’ her new bottled water and felt anxious about the prospect of consuming something else. Virtually all of the respondents felt the substitutes were inferior in quality in spite of the fact they were exactly the same.

It became apparent, that a strong brand identity primes consumers towards a more positive experience. One young man felt that if you wore Nike whilst playing football, ‘you look the part’ and nobody would subsequently question your ability on the field. He felt wearing Nike lifted his game.

Others relished the fact that their favourite shampoo made them feel like Don Draper!

It was evident that priming plays a fundamental part in driving the whole brand experience.

Heuristics:

Brands provide hugely important mental shortcuts (heuristics) and can convey a rich brand heritage through nothing more than a logo. We witnessed a lady talk at length about the heritage of Yorkshire tea. She spoke of the evocative imagery that the brand conveys though its packaging and described it as a ‘proper brew’, which is the language used in the ads.

The ‘love it/hate it’ marketing concept of Marmite was discussed at length by a Marmite-lover who felt the product didn’t taste the same in different packaging. The yellow lid was a symbol of quality and reassurance – that each brand experience would be consistently positive.

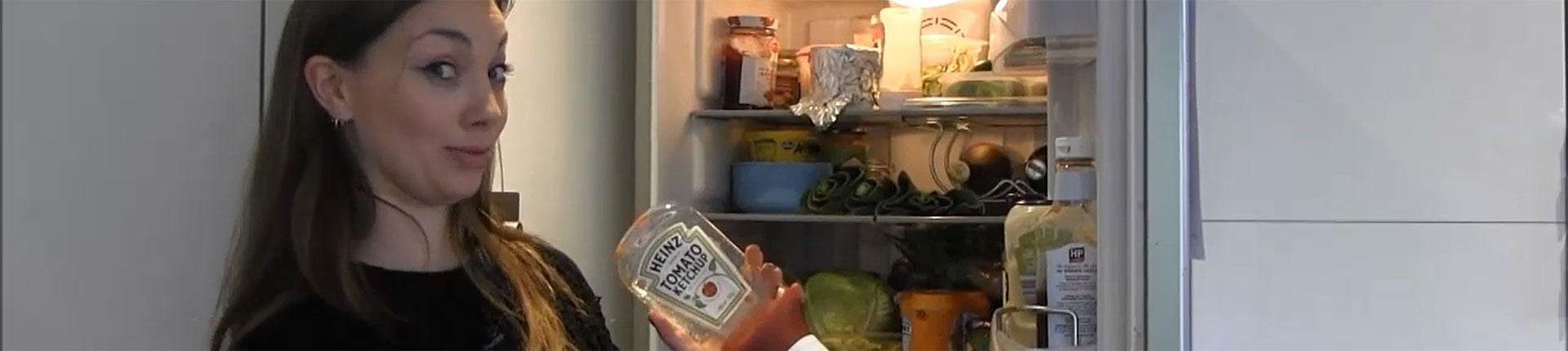

We witnessed high levels of commitment bias, where brands had built a deep behavioural connection around their brand. One example of this was with Heinz Ketchup, where people mentioned the ‘need’ to put it on their ‘beige food’ and how a substitute ketchup is inherently less attractive; ‘it has to be Heinz’. Advertising – and particularly TV advertising – creates these heuristics and gives the brand a host of positive attributes that can set it well apart from its competitors.

Anchoring:

In behavioural economic terms, brands provide a crucial ‘anchor’ for consumers. People make snap judgements and ‘anchor’ their decisions based on the initial information they receive. This was immediately evident in our experiment.

Not one of respondents felt enthused about their replacement products. Such was the power of the anchor effect that when their beloved brands were removed, they swore the ‘new’ products were inferior even though they were using exactly the same things!

Interestingly, many of the reactions were physical. A woman swore her de-branded dry shampoo felt colder on her head and that her mouthwash didn’t ‘burn’ the same as her usual brand. A man was convinced his ‘new’ shampoo didn’t make his hair squeak with cleanliness like his ‘old’ brand. Fabric softener didn’t leave a lasting smell, tea was weaker and didn’t taste the same’. People felt unenthused about driving their de-branded cars or shopping at comparable retailers.

In every case, the perceived quality was lower.

Loss aversion:

We repeatedly witnessed how brands brought stability to people’s lives in times when they are often less physically connected to their friends and family.

When the brands were taken away, a perceived level of stability was removed alongside them. We witnessed a powerful subconscious desire in our respondents to combat loss aversion (behavioural economics demonstrates how people generally prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains). One woman mentioned how PG tip reminds her of home and how her family have always drunk it. She found comfort in the brand and felt less connected to her family once it was taken away. An older gentleman (with very little hair) used Head and Shoulders as it took him back to the ‘long, luxuriant locks’ of his youth and the way he felt during his ‘Lothario’ days.

One respondent was gutted about driving his de-branded BMW. Although he didn’t need the badging to spot a BMW, he felt might. He associated the BMW brand with success and felt the loss of branding keenly in terms of how he might be perceived by others. Another woman mentioned driving her de-badged car was ‘isolating’.

Each individual started the experiment confident that the task wouldn’t have much of an impact. The reality was significantly different.

In summary

The colour that brands bring to people’s lives becomes starkly obvious as soon as those brands are taken away.

Virtually all of our respondents were staggered to discover they had been using their favourite products, but de-branded. Subconsciously, the de-branded experience dulled the senses, reduced the perceptions of quality and highlighted the ever increasing importance of brands.

Thinkbox

Thinkbox