In Brief

Advertising attention measurement is a hot topic. Thinkbox’s exploration of it began in 2021, and resulted in the publication of ‘Giving attention a little attention’ (2022), a white paper authored by award-winning cognitive scientist Dr Ali Goode which outlined current approaches to attention within the media industry and compared them with approaches taken in academia.

In 2023, we put attention back in the spotlight to build on that white paper and explore how TV ads compete for attention in our lives. We recommissioned Dr Goode specifically to delve into the roles audio and visual signals play in gaining and keeping attention.

Key points

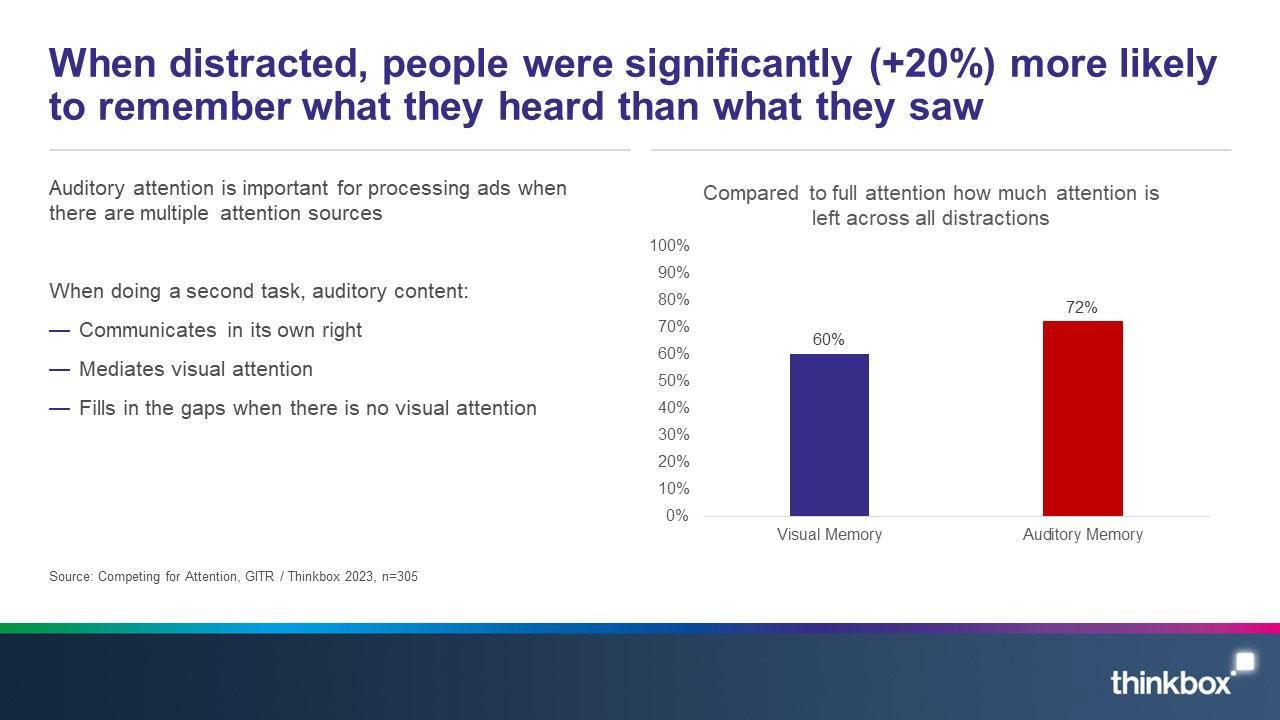

- When distracted, people are significantly (+20%) more likely to remember what they heard than what they saw.

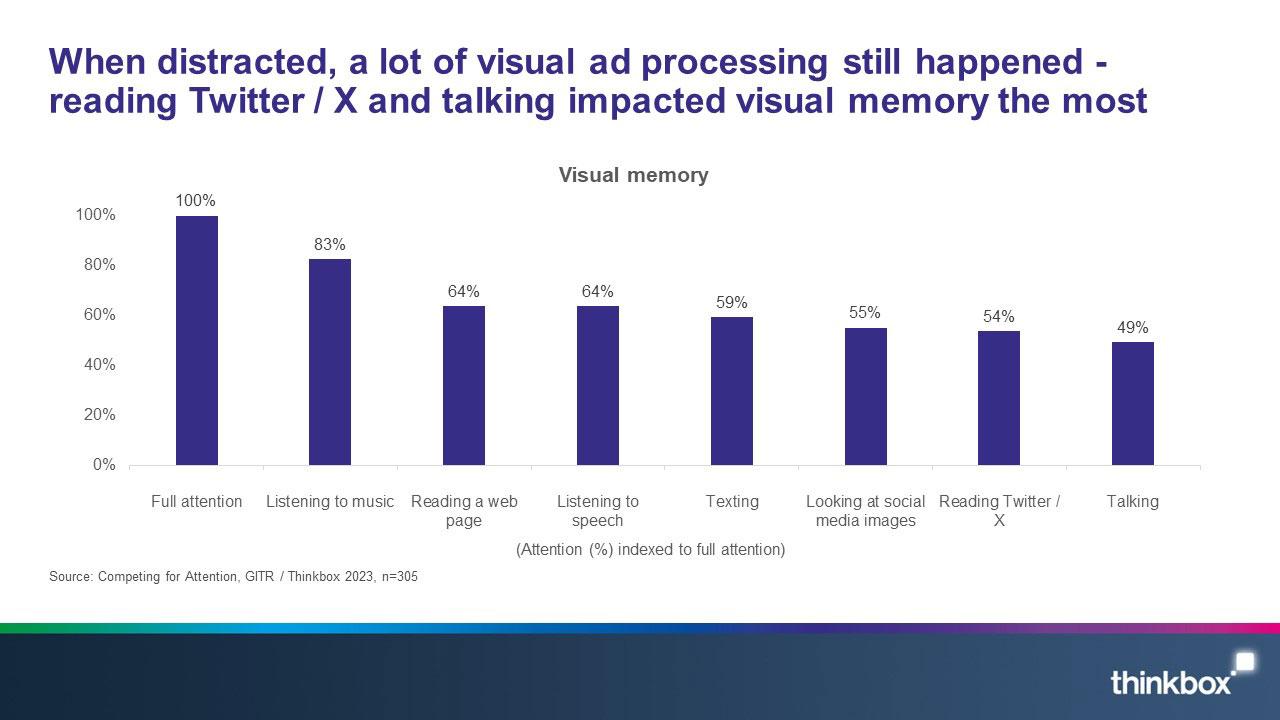

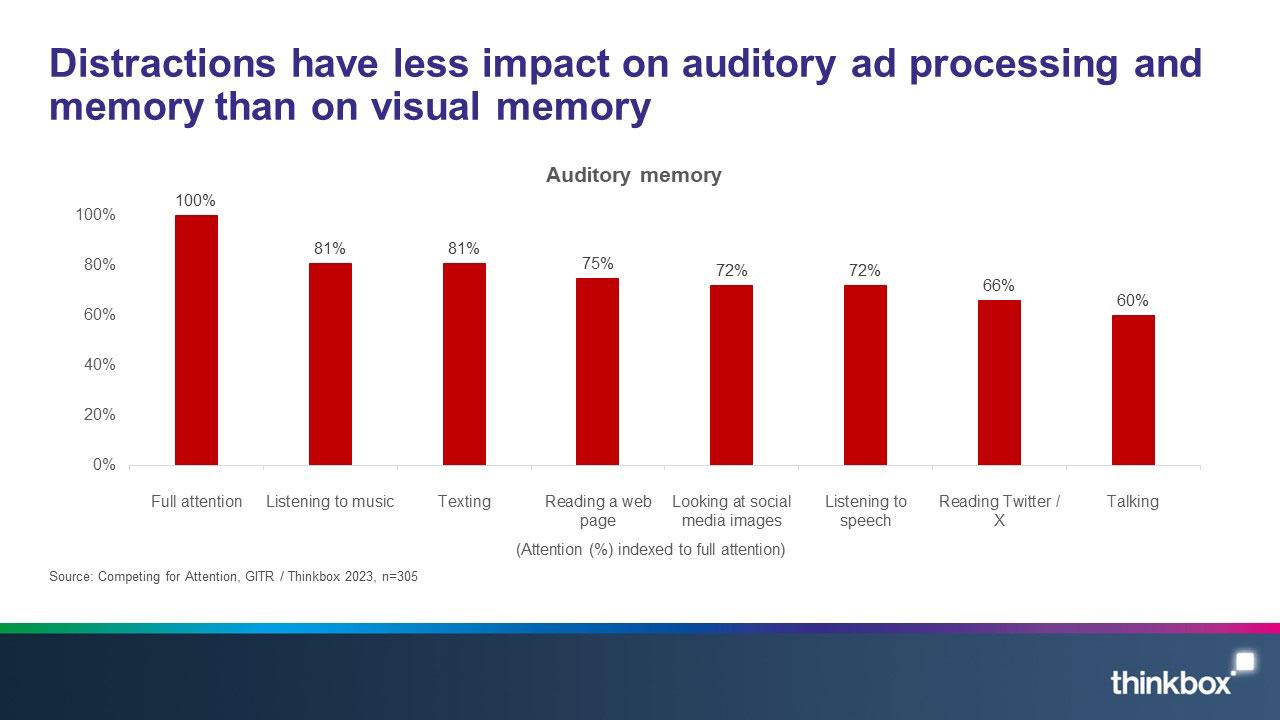

- When distracted, a lot of ad processing still happens.

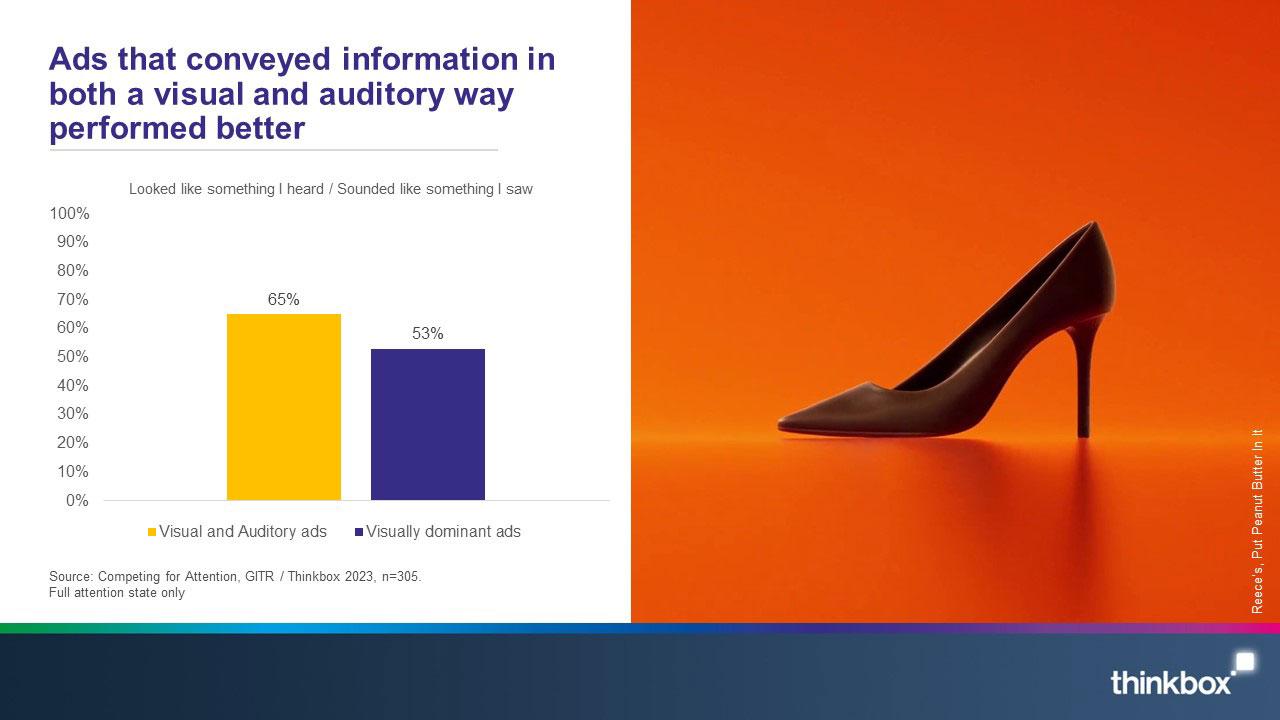

- Ads that conveyed information in both a visual and auditory way performed better.

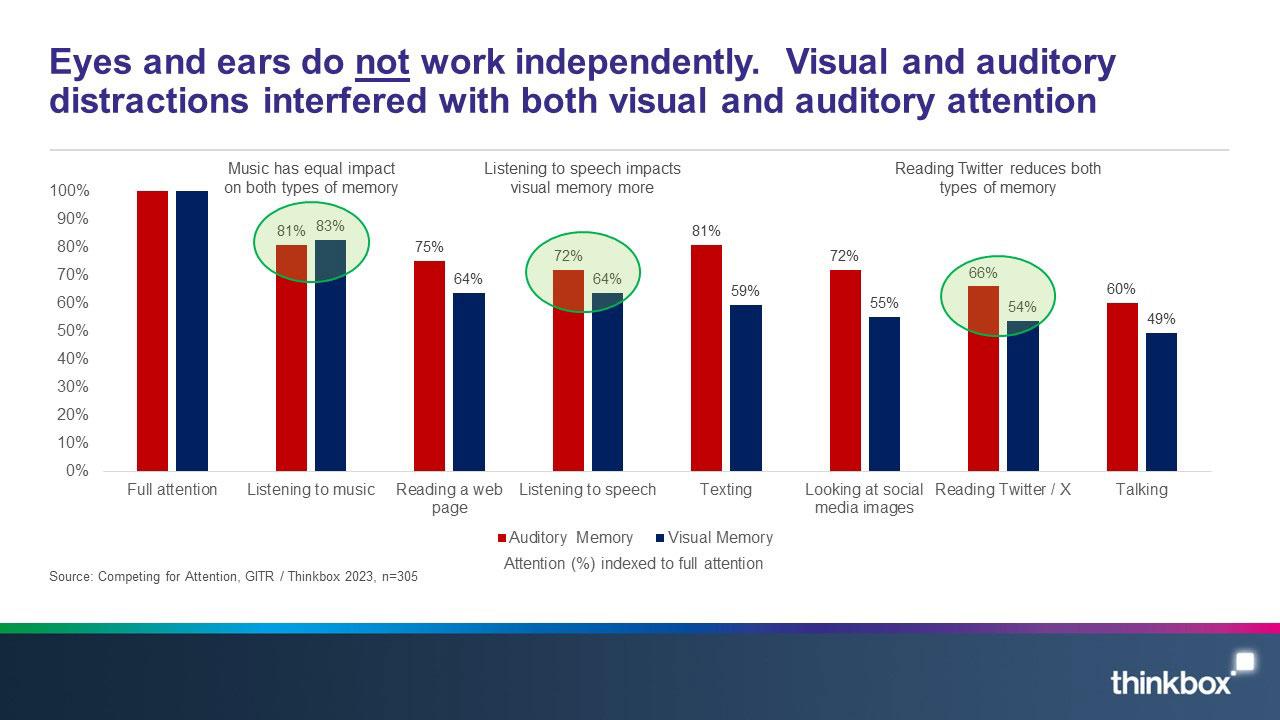

- Eyes and ears do not work independently – memory levels are impacted by total cognitive load.

- Our senses fill in for each other. For auditory content specifically, if vision is elsewhere, sound will carry meaning.

In Depth

Background

Most early explorations of attention focused primarily on visual sensory input. However we live in a multisensory world, so the role of audio also needs to be considered in the attention debate – especially as new attention metrics continue to emerge that are beginning to influence planning and buying decisions. It’s important that they are fit-for-purpose.

In late-2021, we decided to delve into this topic and ‘give attention a little attention’ (published in 2022). We were keen to explore what attention is, what the best way to measure it is, and how understanding more about attention can help advertising be more effective. This first step opened up lots of further avenues to explore. In 2023 we recommissioned Dr Goode to continue the journey.

To start, we revisited earlier unpublished research by ITV in which Goode conducted virtual reality 360° filming of different families in their homes (Oct 2019 – Mar 2020). The content consisted of 17,017 ad exposures (equivalent to 150 hours of ad watching). These exposures were then categorised into three groups and their behaviours while watching TV ads:

Engaged :

- Commenting on the ad’s offer or creative

- Mimicking the ad

- Essentially high attention

Reachable:

- Partially watching ads at high attention

- Divided attention (where they were distracted either visually or auditory)

- Low attention whilst distracted both visually and auditorily

- Watching EPG with sound on

- Sound off but screen can be seen

- Turned TV off or changed channel mid-advert

Unreachable:

- Present but fully distracted

- Fast forwarding

- Left the room or weren’t present.

When respondents were reachable, high attention accounted for 29% of the time. Visual distractions such as second screens accounted for 26% of the time, auditory distractions such as talking accounted for 18%, low/ fragmented attention (such as interruptions by children/pets) accounted for 27%.

Focussing specifically on the non-high attention time within the ‘reachable’ group, our new study (Earning Attention) set out to investigate how much value do ads have when other tasks are also being done at the same time.

Methodology

‘Earning Attention’ was rooted in academia. In addition to Dr Goode’s expertise, we brought on board Professor Polly Dalton, Professor of Cognitive Psychology at Royal Holloway (part of the University of London). Professor Dalton also runs Royal Holloway’s Attention Lab and has published a variety of academic papers on attention.

Following the rigour of academic procedures, Professor Dalton helped develop a number of hypotheses about the likely attentional impact of distractions. Subsequently, we designed tests to prove/disprove the hypotheses, and built a methodology that was rigorous enough to pass the threshold for submission to a peer-reviewed publication (publication is anticipated in 2024).

This large-scale (sample of 305) academic study was designed to assess how much attention can be shared between ads and other ‘distractor’ tasks.

Yonder Data Solutions created a research environment where we had the ability to control all of the respondents’ auditory and visual attention with no other distractions. Respondents were provided with two different tasks on two different devices. An ad would appear on the first screen (acting as the TV screen) synchronised with a task on the second screen. This process was then repeated to cover all the test ads and distractions. Respondents were forced to divide their attention between two different tasks – and tested on their memory of both.

For the stimulus, the ads featured were for familiar brands and in English originating from the United States, Australia and Canada (and so never seen before in the UK). In order to create a convincing ad break, a range of different brands were used. They were a combination of ‘visual only’ (ads that had a soundtrack but carried little information e.g. no voiceover) and ‘auditory and visual’ ads. With the help of System1, we acquired a range of good, medium, and ‘bad’ ads from a range of product categories.

The distractor tasks were identified using IPA TouchPoints to determine the most common activities done whilst watching television e.g. listening to music, looking at images (Instagram), listening to speech, reading social media (Twitter/X), reading a web page, texting and talking. We also tested with no distraction, which was used as a baseline.

Results were determined via ad memory testing (recognition) as an indication of what respondents’ attention ‘let through’. To test visual memory, respondents were shown 24 images from ads they had been exposed to, as well as a set of control images for ads that had not been included in the study, and were asked whether they had seen the image in one of the ads. Similar questions were asked to test auditory memory after respondents heard 24 audio clips.

Findings

How important is what you hear?

The research suggests that when people had been distracted, they were more likely to remember things they heard rather than what they had seen. The role of sound plays an important part of the TV ad experience. Sound has the ability to communicate in its own right, it can mediate attention and draw eyes to the screen and fill in the gaps when there is no visual attention.

Audio stimuli are important in human behaviour as ears are permanently ‘open’. As a result, we should expect people to be able to process and retain spoken messages (e.g. phrases or propositions), sonic or unique brand assets (e.g. Intel sting, McDonald’s whistle, Confused.com guitar riff), sonic cues that communicate meaning (e.g. loud noises/alerts, celebrity voices, emotional vocalisations), music driving the creative (that they sing/dance along which becomes associated with brands), or jingles.

Essentially, we don’t look around for things to listen to, instead our ears tell us where to look. Data shows that when distracted, people were significantly (+20%) more likely to remember what they heard than what they saw.

How much attention is left over for ad processing when people do other stuff?

Analysis found that the tasks (distractions) affected the amount of attention available for visual and auditory processing of an ad. ‘Talking’ was the most attention-demanding task in comparison to ‘listening to music’ on the other end of the spectrum for both auditory and visual memory. We found that the amount of effort taken up by the distraction (attentional/cognitive load) had an impact on the amount of attention left to process the ads, but it is clear that the ads were still processed.

Do eyes and ears work independently?

As individuals, we have a finite amount of attentional resource. As a result this attentional load is shared around the senses. Other tasks will deplete the amount of attention we have left regardless of the sense being used to do it.

Analysis shows that eyes and ears do not work independently and that visual and auditory distractions interfered with both visual and auditory attention. As a result memory levels are impacted by total cognitive load.

Are ads better when they are multisensory?

To explore this sense interdependency, we looked at whether a multisensory experience has an impact on attention.

The respondents were shown one of the ads at high attention (i.e. no distractions) and were asked whether they had seen a particular image from that ad. However, if respondents had low confidence about what they had seen, they were further prompted about whether they had heard something that would have looked like that image.

Conversely, if respondents had low confidence about what they had heard, they were prompted about whether they had seen something that looked like the sound that was played. This recognition technique was used in order to gain a better understanding on whether people were going to be using both senses to understand an ad in its entirety.

Analysis found that ads conveying information in both a visual and auditory way performed better. It’s the combination of the auditory and visual experience that allows individuals to piece together a narrative – and the same seems to be true for ads. This suggests that when the respondents were not sure if they had seen or heard an ad, they used another sense to assist in establishing whether it had been experienced.

Essentially, there’s an advantage when ads communicate in a multisensory way. We combine what we see and hear to process an ad and use sound and vision to fill in for each other to subsequently form a narrative.

Our senses fill in for each other. For auditory content specifically, if vision is elsewhere, sound will carry meaning. When people hear a sound they recognise, they will know what it looks like e.g. Go Compare, Snap, Crackle and Pop, etc. People can use auditory cues to follow a narrative for both new and previously seen ads. In addition, music that drives the creative or the narrative is better than background music; the auditory carries it through, even though the visual attention isn’t there.

The analysis from the 2022 white paper (‘Giving attention a little attention’) showcased the importance of auditory content. The 2023 study clearly shows that if this element is not maximised to its full potential, there may be lost opportunities because auditory content is more important than visual when people are distracted as it is more resilient. The study also brings to light the importance of making the most of a multisensory ad experience, in order to maximise the opportunity to gain the most attention.

In summary

Whilst attention is a complex topic, this research showcases the importance of both visual and auditory attention and advocates the use of audio and visual stimuli together when forming a narrative.

Sound, when used effectively can communicate in its own right, mediate visual attention and fill in the gaps when there is no visual attention.

This study contributes to the long-standing attention debate and helps give audio the recognition it deserves within AV content.

Thinkbox

Thinkbox